Top 7 Code and Software Documentation Best Practises For Engineering Teams

TLDR;

- Enterprise teams lose the most time and quality due to undocumented engineering intent. When the reasoning behind system behaviour disappears, developers rely on assumptions, which increases defect risk and slows new work.

- Review cycles stretch when reviewers cannot confirm whether a change respects earlier constraints or past decisions buried in old threads, files, or PRs. Zenhub’s data shows missing context is a major contributor to sprint delays.

- Engineers across large companies consistently report that deep system behaviour is poorly documented. Process docs and style guides exist, but the underlying “why this works this way” is rarely captured in a durable, searchable form.

- Missing or outdated documentation leads to repeated architectural debates, regressions introduced during refactors, and production incidents caused by unseen edge cases. These issues accumulate quietly in large codebases until the impact becomes visible.

- AI-driven code review tools help break this cycle by surfacing hidden dependencies, past decisions, invariants, and behavioural patterns directly in the review workflow. Qodo extends this advantage by pairing code diffs with historical context, documentation traces, diagrams, and previous PRs, allowing reviewers to validate intent without reconstructing it manually

In enterprise teams, the largest documentation gap stems from missing engineering intent, the “why” behind the decisions that shaped the system. . When that intent disappears across 10 repos or 1000, teams lose the context required to maintain coherence at scale. Engineers spend significant time reconstructing past decisions instead of advancing current work, and that lost time multiplies across 15+ workflows that depend on shared components.

This directly increases defect risk: a study in the Journal of Systems and Software reported that unclear or missing documentation leads to higher defect density because developers routinely misinterpret expected behaviour during updates.

Zenhub’s engineering report found that developers lose a significant portion of every sprint due to missing context, unclear instructions, and undocumented assumptions, all of which slow down code reviews and force repeated clarification cycles.Reviewers pause on simple diffs not because the code is unclear, but because they cannot confirm whether the change aligns with domain rules, performance expectations, or architectural constraints that were never properly captured.

As Itamar Friedman explains:

“The end goal isn’t faster code writing. The end goal is better software, faster software. That’s why you start seeing serious investment in code review and testing, not just code generation.”

This is the deeper issue facing enterprise engineering today: speed is no longer the bottleneck; missing intent is. When teams cannot see why a decision was made, they repeat past debates, reintroduce previously fixed bugs, and spend days restoring context that should have been documented once. This gap also creates a silent quality risk, reviewers hesitate to approve changes when they cannot see the historical reasoning behind them.

This blog will walk through the top seven code and software documentation best practices that help restore clarity, improve cross-team alignment, and improve overall code quality in enterprise environments.

The Problems Developers Face When Documentation Is Weak

Before getting into the best practices, it is important to understand the specific issues poor documentation creates inside enterprise codebases. These are not abstract inconveniences; they show up as slower reviews, higher defect rates, repeated implementation mistakes, and longer onboarding cycles.

Here are the problems specifically:

- Code Complexity Increases Faster Than Engineers Can Keep Up

- Design Reasoning Goes Missing

- Cross-Repo Inconsistency Amplifies Complexity

- AI-Generated Code Adds Another Layer of Variance

- Architectural Decisions Get Lost

- Undocumented Edge Cases Lead to Production Incidents

In large teams, the absence of clear documentation becomes a measurable bottleneck because every engineer depends on shared context to make correct decisions. The following points outline the problems I have consistently encountered while working across complex systems and distributed teams.

1. Code Complexity Increases Faster Than Engineers Can Keep Up

I have seen complex modules become unmanageable simply because the original design reasoning was never documented. In one enterprise system I worked on, a critical billing function required almost two days of developer time to trace because no one had documented why certain conditional branches existed. The Journal of Systems and Software reinforces this pattern: missing documentation increases defect density because developers are forced to rely on assumptions instead of verified behavioural intent.

This is a practical problem in large teams. When developers do not have a written reference for logic boundaries, they make cautious but incorrect changes that introduce regressions. Code complexity keeps rising not due to poor skills but because the foundational context that keeps code stable is missing.

2. Design Reasoning Goes Missing

Across enterprises with 50+ engineering teams, the pace of change consistently outstrips the preservation of design decisions. Modules become difficult to evolve because the original reasoning: the constraints, trade-offs, and intent, was never recorded or has faded as teams changed ownership.

Every undocumented decision forces engineers to reconstruct history before taking action, slowing throughput and increasing the likelihood of misalignment with broader architectural goals.

3. Cross-Repo Inconsistency Amplifies Complexity

Complexity speeds up at enterprise scale because services span multiple repositories, ownership boundaries, and development standards. Cross-repo inconsistency quickly becomes structural debt. One team documents invariants thoroughly; another leaves them implicit. A downstream service may depend on constraints stored in an entirely separate repository with no shared reference.

Without a unified documentation structure, engineers reconstruct logic relationships manually. This increases the likelihood of regressions introduced through misunderstood boundaries.

4. AI-Generated Code Adds Another Layer of Variance

AI-generated code creates its own form of divergence inside large organisations. Teams adopt AI-assisted workflows at different maturity levels, resulting in uneven patterns across services. Some repositories receive highly optimised but unconventional implementations; others receive conservative, pattern-based output.

When documentation does not capture intended behaviour, constraints, and invariants, these AI-driven variations accumulate at scale. The rising complexity does not reflect a lack of developer skill, it reflects the absence of a shared, written foundation that keeps distributed systems coherent.

5. Architectural Decisions Get Lost

In one architecture review, we spent a full meeting debating whether to adopt a shared authentication layer for two services. After an hour of discussion, someone found an old Markdown-based Architecture Decision Record (ADR) created two years earlier showing that the company had already made the same decision, and rejected it due to compliance constraints. The document was hidden in an archived folder no one maintained.

This is common across enterprise codebases. When design decisions are undocumented or scattered across outdated channels, teams unknowingly repeat past arguments, reverse previous choices, or reintroduce previously fixed issues. The cost is measurable in wasted meeting hours and unnecessary rework.

6. Undocumented Edge Cases Lead to Production Incidents

One of the most expensive production incidents I handled was caused by an undocumented edge case in a data ingestion workflow. The original engineer had implemented a defensive check for malformed payloads, but the purpose and conditions were never written down.

A new engineer removed it during refactoring, assuming it was redundant. The result was a cascading ingestion failure and a multi-hour recovery window. Edge cases are invisible until they break. Without documentation, engineers remove safeguards they never knew existed.

Top 7 Best Practices for Code and Software Documentation

Strong documentation is not created by chance. It improves when teams follow a clear group of habits that remove ambiguity and preserve context across the codebase. The practices below are the ones I rely on in enterprise environments because they reduce review friction, shorten onboarding time, and maintain consistent code quality across services. Each practice is supported with real examples to show how it works in day-to-day engineering work.

1. Enable AI-Assisted Reviews With Version-Controlled Documentation

In large engineering organizations, documentation that governs system behaviour cannot remain in scattered wikis, outdated Confluence pages, or Jira tickets detached from the current release. When this information drifts, teams managing 10 repos or 1000 face onboarding gaps, review delays, and workflow inconsistencies that compound across 15+ interconnected pipelines. Engineers follow the available instructions, but the instructions themselves become a liability when they are not versioned alongside the code.

To avoid this drift, enterprises store all behaviour-defining documentation directly in the repository. Architectural notes, invariants, data contracts, and integration rules must evolve with the implementation.

When documentation changes through the same pull request as the code, reviewers understand intent, developers have fewer clarifications, and systems remain stable as ownership shifts across teams.

AI adoption has made this discipline even more critical. As developers use AI tools to write or refactor code, review cycles often bring up inconsistencies between generated logic and the documented expectations for domain behaviour.

AI may create correct syntax while quietly violating constraints that were never properly recorded. Version-controlled documentation gives AI review systems the grounding they need to detect these mismatches accurately.

This is exactly where Qodo strengthens enterprise reliability. Qodo is an AI code review platform that evaluates changes from a clean-slate perspective, using multi-repo context and documented intent to bring up inconsistencies before they become defects. It acts as the missing quality layer between AI generated code and the standards required for production-grade systems.

As Lotem Fridman from monday.com explains:

“An AI agent that goes and reviews the code from a clean-slate perspective is very valuable. We see it catching bugs – and that’s what’s important in the end.”

With documentation versioned in Git, Qodo’s review engine can validate whether each change aligns with system intent, architectural constraints, and historical decisions, ensuring that AI-generated or human-written code does not drift away from how the system is supposed to behave.

This small CI rule helped enforce consistency:

# Block PRs that modify code but skip documentation if git diff --name-only origin/main...HEAD | grep -E "src/|api/"; then if ! git diff --name-only origin/main...HEAD | grep -q "docs/"; then echo "Update documentation for your change." exit 1 fi fi

Platforms like Qodo make this workflow even cleaner because the reviewer sees the code diff and the doc diff side-by-side, along with relevant historical context pulled automatically from previous changes. This prevents undocumented behaviour from sneaking into production.

Know Your Audience Before You Write Anything

The biggest documentation problem I see in enterprise teams is writing for a generic reader who doesn’t exist. Backend engineers want constraints, invariants, and architectural decisions. Product teams want outcomes and behaviour. Operations teams want failure patterns and recovery steps. If I mix those audiences, no one gets the detail they actually need.

When I document a new service, I create two layers:

- Engineering-focused documentation: such as Architecture Decision Records (ADRs), service architecture overviews, sequence diagrams, data contracts, and integration notes. These documents capture the internal reasoning, constraints, and invariants that engineers rely on during reviews and refactors.

- Functional documentation: how the feature behaves from a business point of view.

Here is an example structure I use inside large repos:

docs/ index.md # simple overview for non-engineers architecture/ # developer-facing docs overview.md sequence-diagrams.md invariants.md operations/ runbook.md failure-modes.md

This structure keeps review cycles tight because reviewers who understand the system can evaluate my changes in context, and non-technical readers never get lost in implementation details.

Make Documentation Easy to Navigate

Documentation fails when someone has to “hunt” for information. In enterprise systems, engineers jump between services constantly, and every minute wasted looking for the right page adds friction to the entire SDLC.

To avoid this, I write every document as if someone will need it during an incident, minimal scrolling, predictable sections, and clear headings.

For workflows that are highly visual or involve several moving parts, I include short video walk-throughs or architecture board captures. Engineers use these as quick references during automated code reviews because they communicate behaviour faster than paragraphs.

Use Visuals to Explain Flows and Dependencies

Text alone breaks down once a system spans multiple services. Distributed flows, retry behaviour, idempotency rules, and cross-service dependencies need a diagram, otherwise engineers interpret them differently.

I once had a refactor break a payment retry mechanism simply because the engineer didn’t realise that retry #2 triggers a downstream idempotent handler. That rule was explained verbally years earlier but never visualised.

A simple sequence diagram solved the entire class of confusion:

User → API Gateway → Payments Service Payments Service → Retry Worker (if failure) Retry Worker → Payments Service (attempt #2) Payments Service → Idempotency Guard → Charge Processor

After I added this diagram to the repo, reviewers could immediately tell if a change respected the retry semantics. When diagrams sit next to the code, review accuracy improves dramatically because reviewers are validating behaviour, not guessing intent.

Standardise Documentation Through a Style Guide

In enterprise environments, inconsistent documentation becomes technical debt. Every engineer writes differently; every team uses different terminology; every document evolves in its own direction. When the system grows, these inconsistencies force future engineers to re-learn patterns they shouldn’t have to.

I built a lightweight style guide that includes:

- consistent naming conventions for domain objects

- rules for describing API contracts

- formatting rules for error scenarios

- where to place diagrams

- how to document invariants vs. assumptions

- how to list prerequisites and environment flags

It looks like this:

# docs/style-guide.md 1. Start each doc with purpose + scope. 2. For APIs: document input, output, side effects. 3. Always document invariants using "This must always hold:". 4. Use "Prerequisites" for environment flags and required secrets. 5. For workflows: include a diagram under 150 lines of text. 6. Write in the active voice, technical tone.

This style guide reduced reviewer confusion, prevented duplicated documentation sections, and made reading any service doc feel familiar.

Keep Documentation Current Through Scheduled Reviews

Nothing breaks trust faster than outdated documentation. An engineer relies on a document, implements something accordingly, and production chaos follows. I’ve seen it too many times.

To avoid this, I schedule documentation reviews in three places:

- Every feature PR: docs updated alongside code.

- Every release cycle: docs reviewed for accuracy.

- Quarterly deep review: remove obsolete diagrams, deprecated flags, or legacy services.

I also run a simple script that flags links or file references that no longer exist:

find docs -type f -name "*.md" -exec grep -H "api/v1" {} \;

This catches outdated references after an API upgrade. Review tools today help here as well. When I open a PR in Qodo, it shows the reviewer all past PRs that touched the same files, including outdated docs. This context makes it easy to catch mismatches early.

Make Documentation a Shared Responsibility

Single-owner documentation is almost guaranteed to fall out of sync. The engineer who wrote it moves to another team, and the document becomes a fossil.

I shift the responsibility onto whoever touches the system. If someone updates business logic, they update the behaviour section. If someone adds a new environment variable, they update prerequisites. If someone discovers a missed edge case, they add an invariant.

Here is an example of a “context note” I encourage engineers to write:

# docs/context-notes/2025-07-billing-invariant.md The tax-calculation service must never call the discount-engine directly. It introduces a circular dependency that caused a production freeze in 2022. Keep the discount call in the aggregator, not the billing service.

This kind of documentation carries the engineering history that prevents repeated mistakes. Reviewers see this during PRs and immediately understand whether the change violates prior decisions.

Over time, these small notes become the most valuable engineering resource in the repository because they encode context that would otherwise vanish.

Code Quality Across the SDLC Depends on Strong Documentation

In enterprise systems, code quality does not depend only on how well a feature is implemented, it depends on how well future engineers can understand, extend, and safely modify that implementation. I learned early in my career that even clean, well-structured code loses value if the surrounding documentation is weak, because code alone rarely carries the entire story.

Decisions, assumptions, side effects, failure modes, and integration behaviour often live outside the function body, and when those details are missing, the SDLC absorbs the cost at every stage.

Documentation also plays a major role in code review. A reviewer can only validate correctness when the intent is clear. If the reasoning behind an algorithm, retry rule, or schema constraint is absent, a reviewer has to reconstruct the logic from scratch.

That slows review cycles, increases ambiguity, and sometimes leads to reviewers approving changes based on incomplete understanding. I’ve seen code reach production with behaviour that looked correct in isolation but violated an unwritten assumption buried in tribal knowledge. Good documentation eliminates that gap.

This is where context-aware review systems matter. When I use Qodo during reviews, the platform surfaces related files, historical decisions, previous PRs that touched the same logic paths, and even the original motivation behind certain patterns.

I still have to reason about the code myself, but having documented context in front of me reduces the mental load and makes it easier to assess whether a change respects existing invariants. The review becomes more about validating behaviour and less about guessing intent.

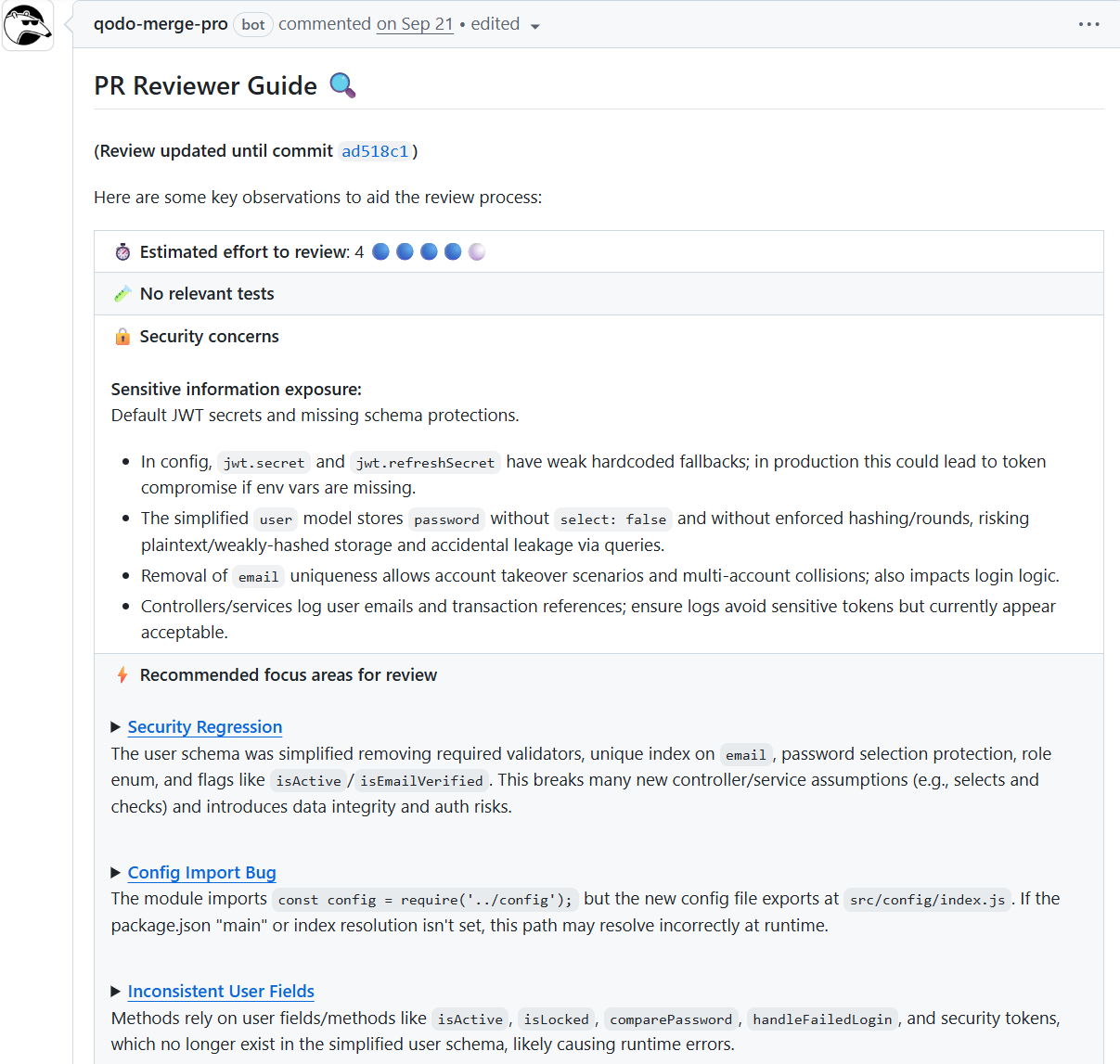

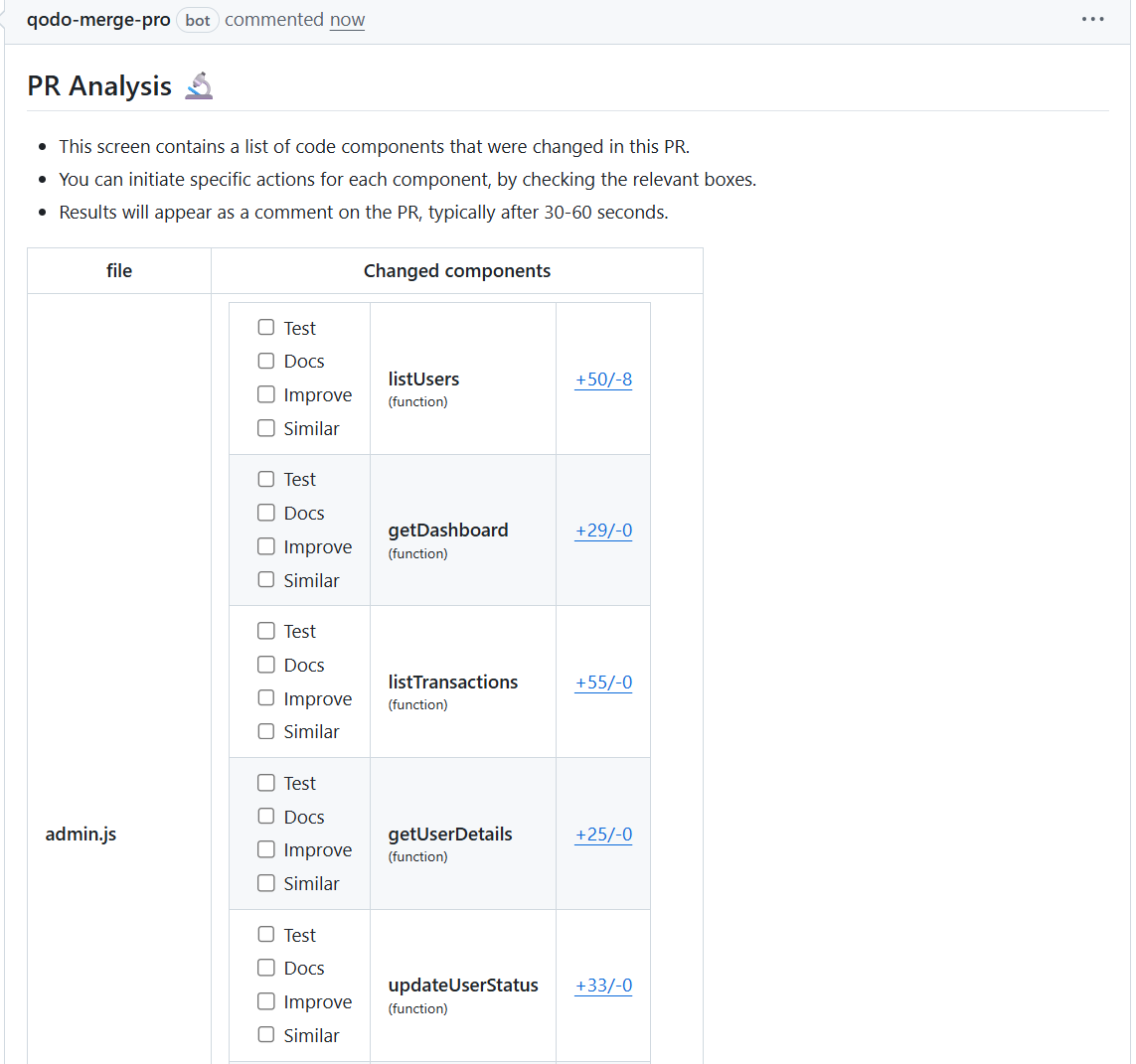

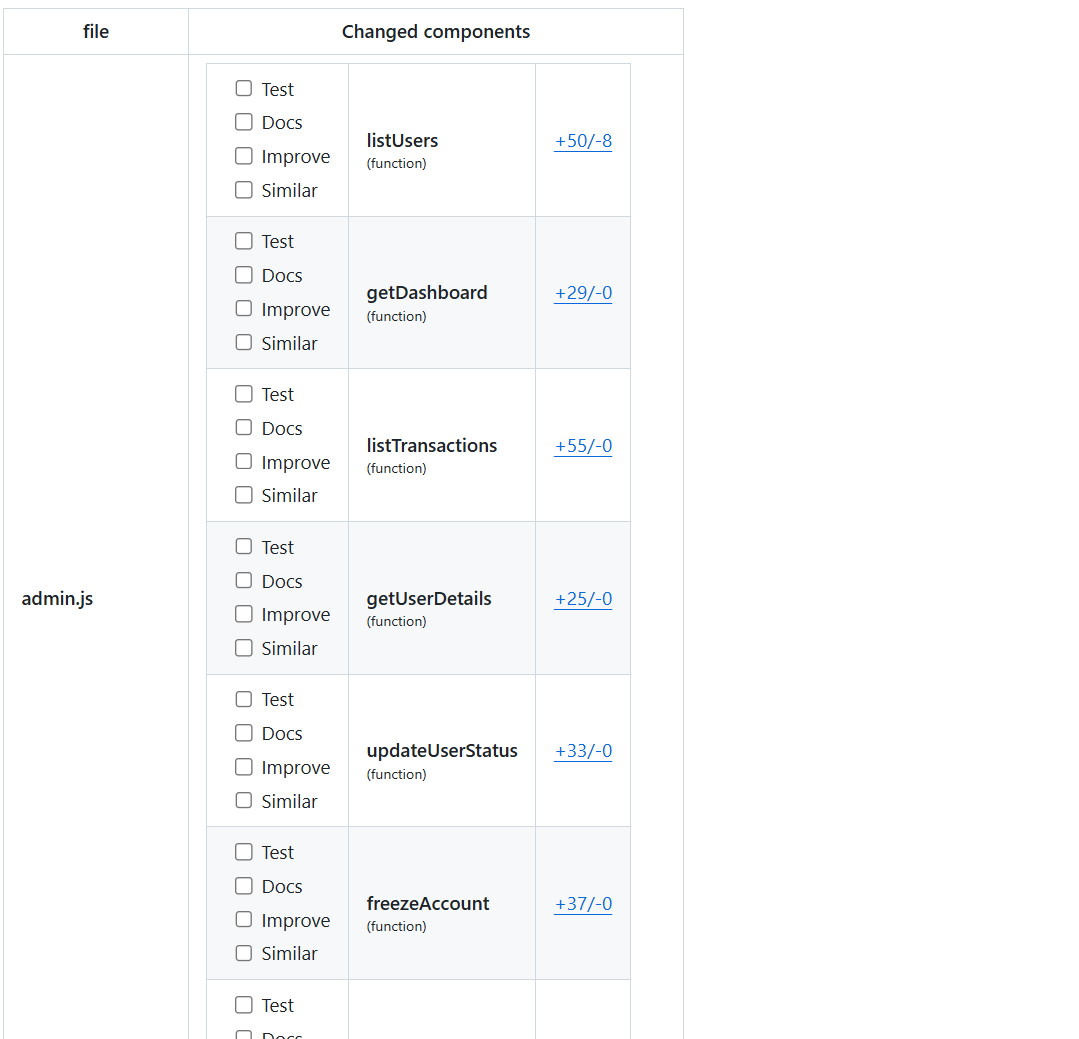

The screenshots above are a practical example of this.

When I look at the first screenshot, I immediately see how impactful the change is: the PR author removed validation layers, stripped security fields, and simplified a user schema without documenting why. Alone, the diff doesn’t show whether this was intentional or a misunderstanding.

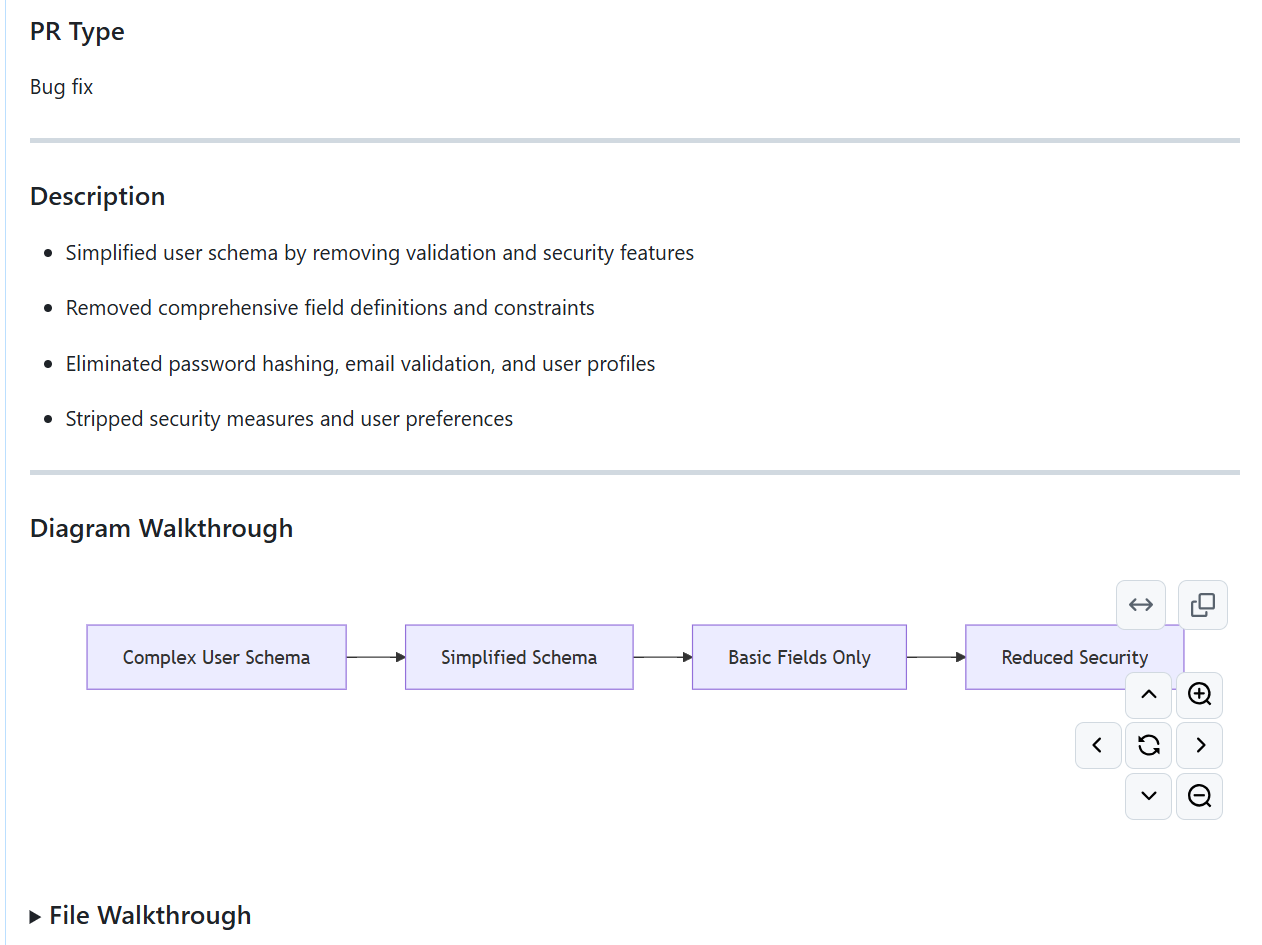

But the review system surfaces a diagram walkthrough showing the path from the original complex schema → simplified schema → reduced fields → degraded security. Here’s a snapshot of the description:

As a reviewer, this visual context tells me something is off before I even open the code. No one simplifies user models for a bug fix unless they misunderstood the design or skipped reading documentation.

This is the type of situation that causes security regressions months later. With good documentation, this type of change would never reach review in the first place. Without documentation, a junior developer can unknowingly delete entire protection layers because they think they’re “cleaning unused fields”.

I asked Qodo to build the change logs and release notes directly from the pull request. All I did was submit the PR, and Qodo analysed every component touched in the update, functions like listUsers, getDashboard, listTransactions, updateUserStatus, and freezeAccount.

In return, it created a structured report showing each function changed, how many lines were added or removed, whether tests were missing, whether documentation needed updates, and whether any improvement opportunities existed. This was not a generic diff. The platform broke the PR down into its behavioural components and turned that into a ready-to-use change log.

It also generated release-grade summaries automatically. Instead of the usual “bug fixes and small updates,” Qodo created a clear explanation of what changed in each functional area of the system. If the PR modified account-level behaviour or altered how a dashboard query runs, that detail appeared automatically in the release notes. The system essentially converted code changes into human-readable documentation without needing me to manually draft anything.

This is where the value of a context-aware review platform becomes immediately visible. When documentation is stored alongside the code, the review system can bring up those invariants automatically during the review. The reviewer doesn’t need to remember historical decisions or dig through a wiki. The system highlights the mismatch instantly and phrases the risk in plain technical terms, plaintext password exposure, weakened account protection, inconsistent model fields, and regressions in controller logic.

Conclusion

In my experience, the quality of a codebase is directly tied to the quality of its documentation. When intent, constraints, and edge cases are clearly written down, developers make better decisions, reviewers work with confidence, and changes move through the SDLC without unnecessary friction. When that context is missing, even simple updates become risky because no one can reliably judge how a change affects the rest of the system.

I see documentation as part of the engineering workflow, not an afterthought. It preserves the reasoning behind design choices and gives review tools enough information to bring up issues that would be invisible in a diff alone. When documentation, coding standards, and context-aware reviews work together, teams maintain predictable behaviour across services and avoid the hidden regressions that usually appear months later.

Strong documentation doesn’t slow teams down. It keeps the system understandable, reviewable, and safe to evolve, and that’s what allows enterprise codebases to scale without losing integrity.

FAQs

What is the purpose of code documentation in software development?

Code documentation preserves the reasoning behind how a system behaves so teams can modify components safely and maintain stability over time. It prevents regressions when contributors rotate or services evolve. Qodo strengthens this by surfacing documentation and historical decisions directly during review.

How does poor documentation affect code quality?

Poor documentation forces developers to guess intent, which increases defects and inconsistent patterns. Reviewers struggle to validate changes without clear context. Qodo reduces this by flagging undocumented behaviour and highlighting missing or outdated references in the review workflow.

What should be included in technical documentation for enterprise systems?

Enterprise documentation should cover data flows, invariants, API contracts, architectural diagrams and failure scenarios. These details help reviewers confirm alignment with design intent. Qodo automatically surfaces related contracts and context so reviewers do not miss critical dependencies.

How often should code documentation be updated?

Documentation should be updated in the same pull request that changes the behaviour. Larger systems benefit from periodic audits to remove outdated references. Qodo assists by alerting teams when a code change lacks an accompanying documentation update.

What tools help improve documentation and review accuracy?

Code review tools that provide historical context, dependency insights and documentation lookup improve reviewer accuracy. This is where Qodo adds value by presenting prior decisions and invariants next to the diff. It helps teams validate changes without searching across scattered sources.