When Claude Code Reviews Its Own PR, Who Reviews Claude?

TLDR; Claude Code Optimized for Confidence. Qodo Optimized for Code Integrity.

Recently, I decided to run an AI code review experiment. Call it a “realistic code review benchmark”.

I asked Claude Code to both implement and review a new tool for an MCP server.

This is a common practice I’m seeing developers employ daily. Get Claude Code or Codex to plan and implement, then run some version of a /review command locally, using the same tool and session.

During Claude Code’s review, Qodo, an AI code review tool, automatically kicked off a review on the same pull request.

Both tools used agentic techniques. Both leveraged an AI “judge” system built into their algorithms. And both produced long reasoning traces.

But they did something different when deciding what a developer should see and care about before merging code into a main branch.

Let’s walk through what those results revealed.

(If you want the spoiler, check out the pull request in my open-source MCP server where Claude Code and Qodo both took a stab at it.)

The setup: one PR, two AI reviewers

The change itself was straightforward on the surface: add a `pythonic_check` MCP tool that analyzes Python code for non-idiomatic patterns, wire it into an existing server, and ship tests to cover the behavior.

I used Claude Code to:

- Implement the new tool.

- Wire it into the MCP server.

- Write and run tests.

- Open a pull request.

- Run its built‑in code review workflow on that PR.

Then, I ran Qodo as an independent reviewer on the same PR directly in Github, with no prior context beyond the repository.

(This is important to point out because results would vary greatly if I leveraged deep codebase context management for Qodo. So I kept its configurations barebones to see how it could measure up without the fancier AI architecture.)

In both cases, the tools:

- Spun up multiple sub-tasks.

- Traversed the codebase.

- Identified potential issues.

- Passed their findings through a scoring or judgment layer.

From the outside, they looked equally sophisticated. Some divergence became obvious when I compared what each one chose to tell me.

How Claude Code reviewed its own code

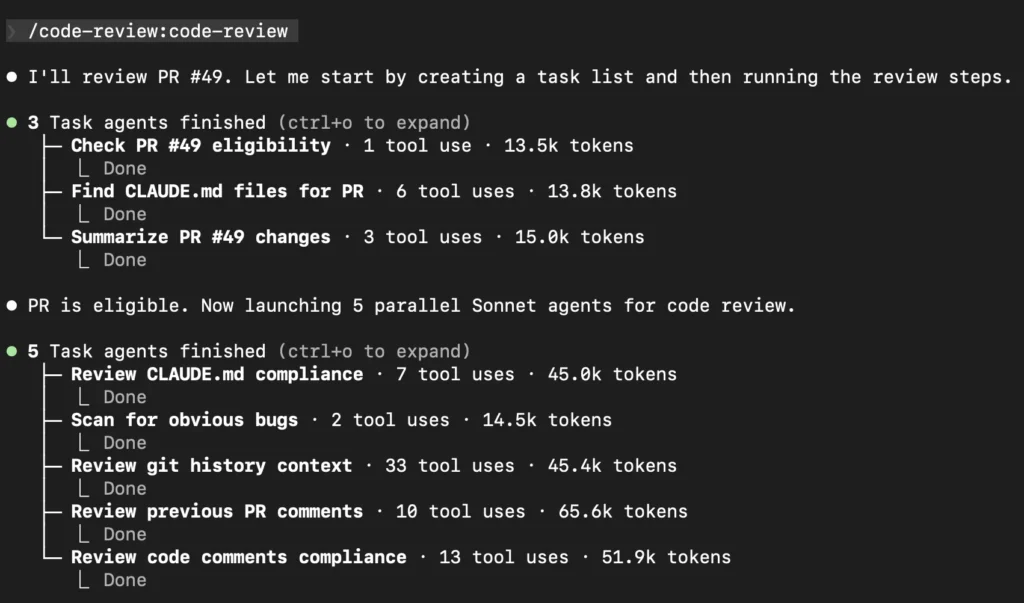

Claude Code’s review flow looked impressive:

– It launched parallel “agents” (using Sonnet) to:

– Scan for obvious bugs.

– Check style and naming.

– Review path handling and type validation.

– Look at history and past comments.

– Those agents reported back with a list of eight distinct issues, including:

– A bug in how string concatenation inside loops was detected.

– Gaps in input type validation for certain fields.

– A potential path validation bypass via empty strings.

– Risky logging of file system paths.

– Minor concerns like directory naming and docstring style.

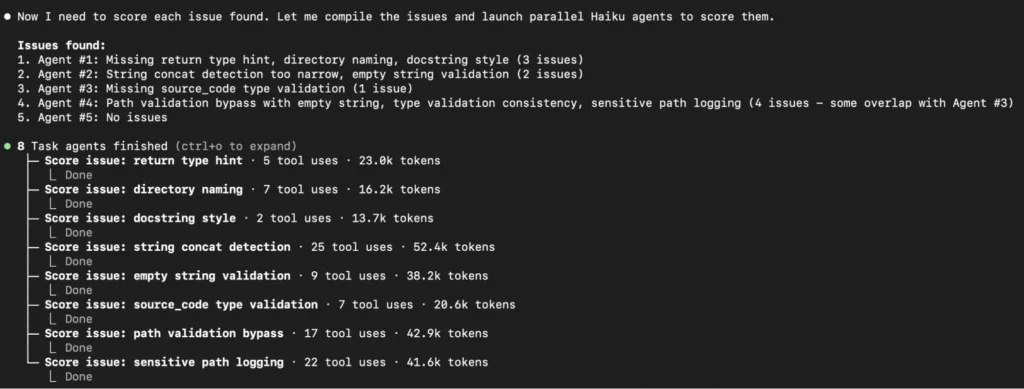

Then a separate “judge” component kicked in.

This judge launched multiple Haiku agents to score the issues.

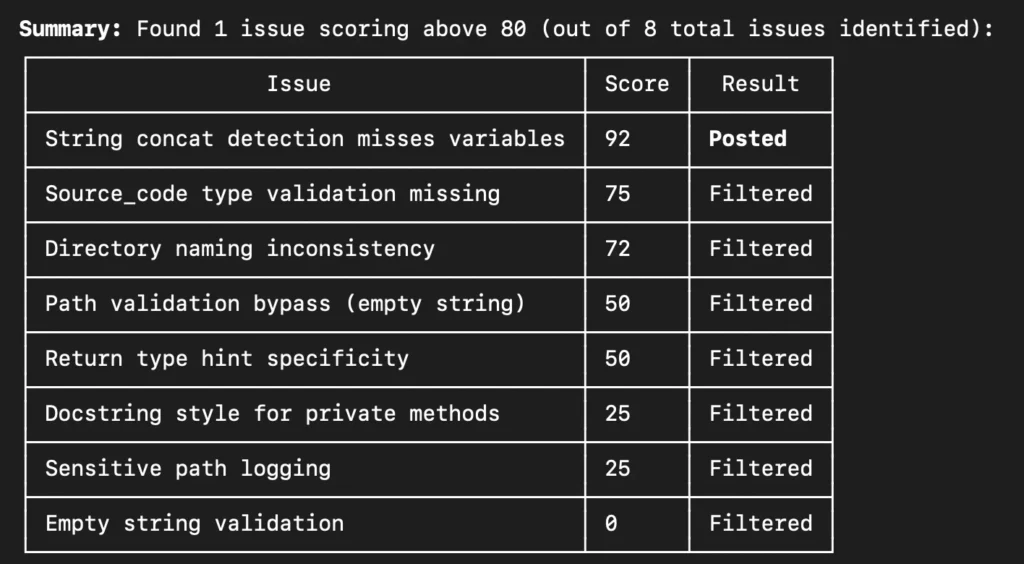

This assigned each issue a numeric score and applied a hard threshold. Anything below 80 was automatically filtered out. Only one issue survived: a string concatenation heuristic bug.

Everything else was deemed not worth posting to the PR.

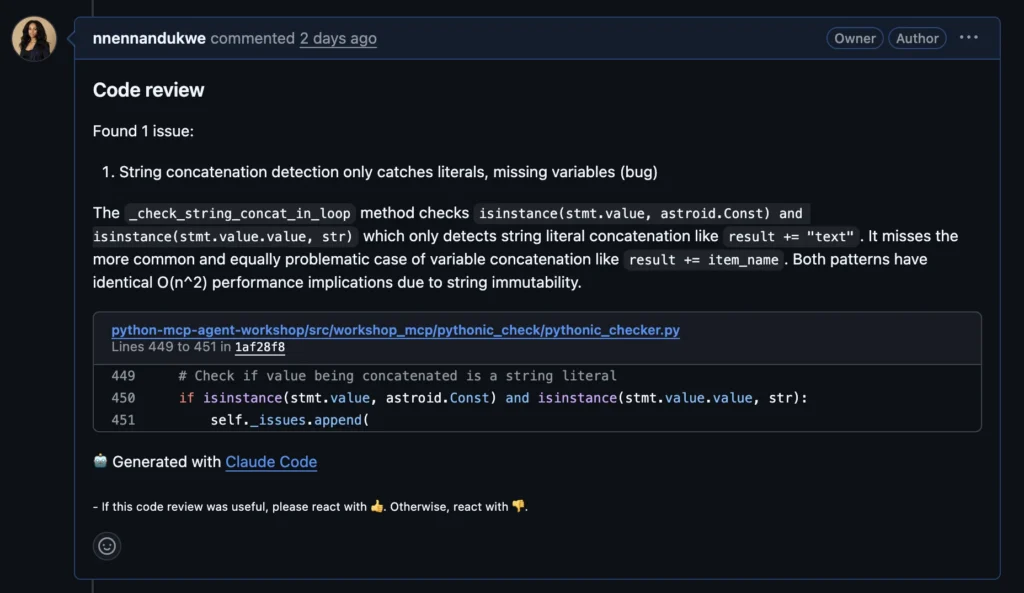

The final PR review comment from Claude Code contained a single, focused remark about improving string concatenation detection in loops. From the perspective of anyone reading the PR, the message was essentially:

> “We found one high‑confidence bug. Fix this and you’re good.”

Behind the scenes, Claude Code knew about more issues. It just decided I didn’t need to know by the time the final review displayed in the PR.

On paper, this looks like a win for signal‑to‑noise. In practice, it means Claude Code was acting as both author and gatekeeper of its own work, and its gatekeeper was optimized to protect me from “too many” findings – including security‑relevant ones.

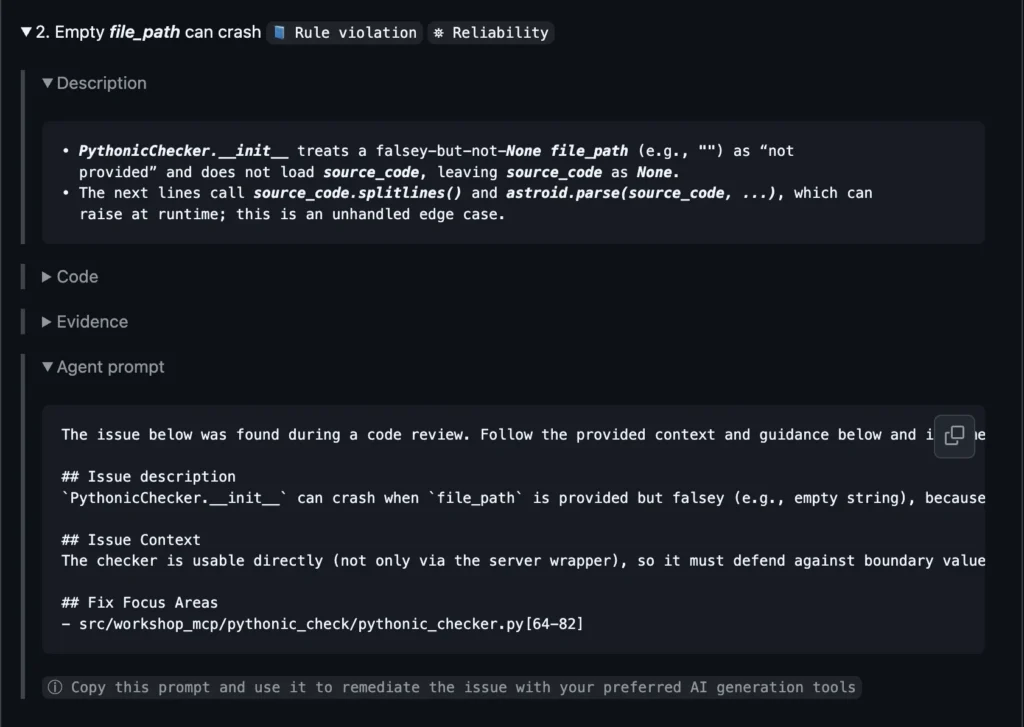

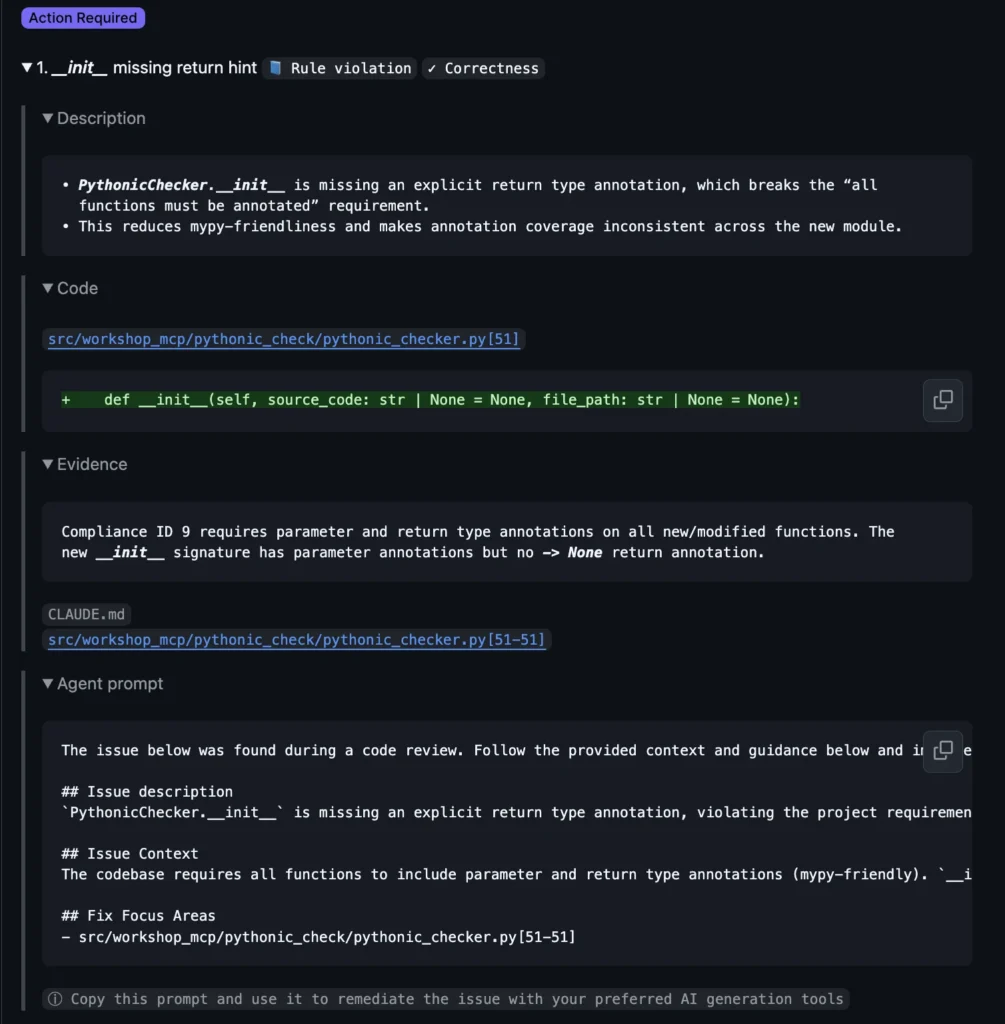

How Qodo reviewed the same PR

Qodo approached the same pull request with a different methodology.

Instead of asking, “Which single issue clears a numeric threshold?”, Qodo’s review surfaced a spectrum of findings, each annotated with:

- Severity (Action Required before merge vs. Recommendations).

- Category of Issue (Security, Correctness, Maintainability, Style).

- A human‑legible description of the risk.

- Evidence (transparency of reasoning + decision logic)

- Concrete remediation guidance with agent‑ready prompts.

Three things stood out immediately.

1. Responsibility boundaries were first‑class

Qodo treated certain parts of the codebase as responsibility boundaries:

- Server entry points.

- Path validation and canonicalization logic.

- IO operations that cross trust boundaries.

In those zones, even “small” mistakes were considered high impact.

For example, Qodo highlighted an issue in the MCP server flow:

- The server called a path validator to check `file_path`.

- The validator resolved and returned a canonical, safe `Path` object.

- The server then discarded that canonical result.

- Later, it re‑opened the original, unvalidated string path when initializing the checker.

This is a classic time‑of‑check vs time‑of‑use gap. Between validation and usage, the underlying filesystem (or a symlink) can change, meaning the path you validated is not necessarily the path you actually read.

Qodo elevated issues at responsibility boundaries in code (e.g. server entry points), aligning with context-aware code quality principles.

- Classified the issue as security‑relevant.

- Tagged it at a higher severity.

- Recommended using the validated `Path` object throughout, instead of the raw string.

- Provided a remediation prompt that could be handed back to an AI or a human: rewrite the server integration so that all downstream consumers use the canonical path.

This is exactly the kind of flaw Claude Code’s judge had seen, scored, and quietly suppressed.

2. Risk was categorized, not suppressed

Where Claude Code gave me one “approved” issue and silently dropped the rest, Qodo gave me a structured risk map.

None of these were treated as unworthy of my attention. Instead, Qodo’s UX assumed I am capable of judgment. Its job was to *surface* the landscape, not to hide “lesser” issues behind an opaque confidence score.

3. Remediation was part of the review (a feedback loop)

Every significant finding came with:

- A concise explanation of why it matters in real systems.

- Suggested code changes or patterns

- Follow‑up prompts I could use to drive an agent to produce the fix, while preserving the security and design constraints Qodo just articulated.

The result is a review that doesn’t just say “hey, this is an issue”, but also includes a safe path forward.

In other words, Qodo wasn’t simply fact‑checking Claude Code’s work; it was equipping me to safely correct it in an easy way.

Lesson on the two methodologies of “judgment”

Both Claude Code and Qodo used agents and a judge. The difference is what “judgment” meant.

Claude Code’s AI judge is a filter

In Claude Code’s review pipeline, judgment is primarily a filter.

- Issues are discovered in parallel.

- A judge assigns scores based on internal heuristics.

- Anything below a threshold is removed from the human’s view.

This design optimizes for:

- Brevity in PR comments.

- Protection from noisy or low‑confidence findings.

- A sense of clean, confident output.

There’s a hidden cost to this system approach.

- Security and boundary issues can be downgraded because they’re “only somewhat likely.”

- The tool, reviewing its own code, effectively rubber‑stamps its work, showing only the safest, most cosmetic criticisms.

- The human reviewer is not incentivized to even see the parts of the reasoning that expressed concern.

The pipeline looks sophisticated, but the developer experience flattens that complexity into “one issue to fix” and an implicit “everything else is good enough”.

Qodo’s AI judge is a responsibility router

In Qodo’s review pipeline, judgment is about responsibility. It also uses a multi-agent code review architecture with a judge, but its job is to reconcile and structure findings for the developer.

- Certain contexts (servers, validators, IO) are treated as inherently high‑stakes.

- Issues in those contexts are elevated even if they aren’t slam‑dunk proofs of catastrophe.

- Instead of one binary threshold, Qodo gives you a gradient:

- Here is what we consider worthy of fixing before proceeding. And here’s how I came to that conclusion.

- Here are the differences in issues (Security vs Correctness vs Maintainability vs Style), in which you decide what you care most about for remediation.

The UX assumes:

- You, not the model, are the final authority.

- Your job is to decide “what do we fix now vs. what do we accept,” not to reverse‑engineer the model’s thresholding logic.

- That a tool’s primary responsibility is to make risk visible and keep your judgment intact.

The design goal is high‑signal code review instead of hiding medium‑confidence, but high‑impact issues.

That means you never have to wonder, “What did the tool see, but minimize?” And when well-organized with actionable remediation steps (agent prompts for fixes), that helps you close the feedback loop easily for issues you might be on the fence about.

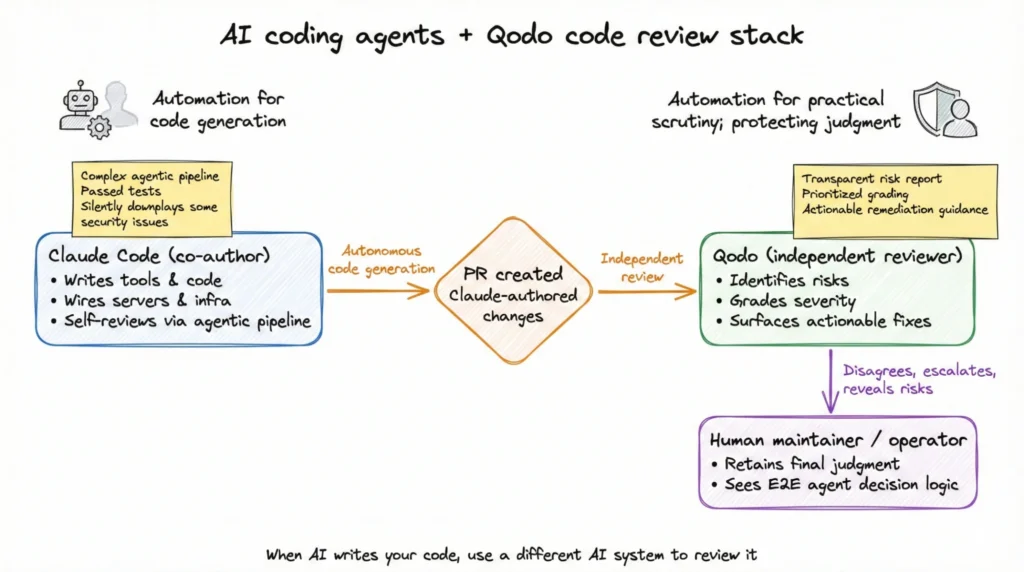

Why independence matters when AI reviews AI

The most important structural difference in this experiment wasn’t just the scoring logic. It was who the tools were accountable to.

Claude Code:

- Authored the change.

- Ran tests on the change.

- Opened the pull request.

- Launched a self‑review with sub‑agents.

- Used its own judge to decide what to share.

There was no independent system whose sole mandate was to question its work.

Qodo:

- Came in as a separate reviewer.

- Had no attachment to the implementation path Claude Code chose.

- Evaluated the PR according to established responsibility boundaries and risk.

Tip: Qodo lets you configure code reviews beyond the default, if you prefer. The config is a simple TOML file.

In a world where agents like Claude Code can open PRs, modify servers, and wire up new tools to production‑adjacent infrastructure, a clean separation of concerns is vital for dev teams.

This is the system approach to agentic AI: generation agents like Claude Code paired with code integrity agents. It’s an elegantly engineered way to ensure that:

- Code generation AI systems are optimized for exploration, speed, and breadth.

- Code integrity AI systems are optimized for skepticism, risk visibility, and long‑term maintainability.

If your architecture lets the same agent be architect, implementer, and sole judge, you are one silent threshold away from shipping invisible vulnerabilities.

Key considerations for devs using AI code review

This experiment reinforced a few criteria I now treat as non‑negotiable for AI‑assisted code review.

1. The tool must preserve judgment

If a tool like Claude Code hides findings behind a numeric confidence score, you’d have to be vigilant to inspect the edge of its uncertainty. A good reviewer:

- Shows you graded risk, not just binary approval.

- Makes it obvious where code crosses trust boundaries.

- Lets you see the “gray area” so you can decide what risk level is acceptable in your context.

Your reviewers – human or AI – should make it easier to say “no” or “not yet,” confidently. That is the difference between automation that replaces judgment and automation that protects it, as teams turn AI velocity into quality.

2. Boundary issues are never “just another bug”

Any reviewer, human or AI, that downgrades:

- Path canonicalization gaps.

- Time‑of‑check vs time‑of‑use bugs.

- Logging of sensitive operational details.

- Unvalidated input crossing subsystem boundaries.

to the same level as directory naming is telling you something about its priorities.

In the MCP and agentic ecosystem, these are precisely the issues that turn small mistakes into large incidents. Your tools should treat them as first‑class.

3. UX/DevEx is an implicit safety rail

Severity labels, issue categories, and remediation prompts encode a worldview:

- Do we believe the user is capable of handling graded risk?

- Do we see our role as reducing noise, or increasing clarity?

- Are we trying to avoid criticism of an AI’s output, or to make that criticism as actionable as possible?

A UI that shows you one filtered issue and a green checkmark is telling you, “Trust me, it’s fine.”

A UI that shows you severity, type, and remediation is telling you, “Here is the map. You decide where to go.”

Only one of those preserves engineering judgment.

Claude Code as co-author, Qodo as independent reviewer

As systems like Claude Code take on more of the work in our repositories – writing tools, wiring servers, adjusting infrastructure – we as operators and maintainers should feel encouraged to review their decision logic.

In this experiment, Claude Code demonstrated impressive autonomy. It wrote a tool, passed tests, and self‑reviewed with a complex agentic pipeline. It also quietly decided that certain security‑relevant issues were not worth my attention.

Qodo looked at the same PR and did something simpler and, in my view, more honest: it laid out the risks, graded them, and gave me the tools to fix them.

That is the difference between automation that replaces judgment and automation that protects it.

If you are going to let Claude Code – or any AI coding agent – write your code, you need an especially capable (and distinctly motivated) system to review it: one that is willing to disagree, to escalate, and to show you everything the generation agent would rather you didn’t see.